Craveology Cafe and the North Star Science Store are temporarily closed for renovation.

by Melissa T. Miller

Forensic scientists are the focus of many television shows, including CSI, Bones, Dexter, and NCIS. But, is it a realistic depiction of the science field? As it happens with many other fields, the number of people and hours involved is often underestimated on screen.

Two real-life forensic scientists can help clear up the differences, starting with the fact that there are many specialized fields within the discipline. One of them is Sydney, a forensic anthropologist that studies bones found on World War II battlefields in order to identify missing service members so that their family members can find some closure. And Roxanne is a criminalist who used to process DNA samples in a lab and now works with technology that’s part of criminal investigations.

In real crime labs, there are major differences in procedure from what is shown on TV, where detectives wander into the lab and ask for tests to be run, then check back in throughout the 1-2 days that it usually takes to solve a case. In reality, detectives and forensic scientists communicate through formal reports, including paperwork to request different tests and to report results.

There are multiple departments with different people who specialize in analyzing chemical evidence, fingerprints or firearms, to name a few. Bones is one of the few shows to actually show a team of people all working on different aspects of the same case. Each person has their own equipment, rather than just one person who manages to “know everything.” To remove the possibility of bias, scientists in one department won’t necessarily know what other departments received as evidence from the same case.

The results of a Google image search for “forensic scientist.” Do these look like accurate representations to you?

“It really is a team of people,” says Sydney. “Even though we’re not necessarily in the same workplace as you see on Bones. We have the DNA people, we have isotope analysis, we have historians who do cultural research and a whole bunch of other things. It’s more of a team effort, you have to bring it all together to be really accurate.”

Another unrealistic aspect of these shows is the amount of time it takes to both gather and analyze evidence. “The processes take really long, it’s not all wrapped up on a 30-minute show,” says Roxanne. “It can take weeks to look at an item of evidence. A lot of the biggest misconceptions have to do with the crime scenes. They can take forever to process.”

Databases usually return multiple search results, unlike the onscreen depiction of having one result ping back almost immediately. They are great tools, but a person still has to go through the results to narrow it down even further. Roxanne says she’s watched shows where, “Once they get the hit it’s like ‘Oh, we solved the case! Bye, we’re done.’ [In reality] that’s just the beginning, an investigative lead.”

There is only so much information the evidence can tell. Sydney remembers one episode of Bones where the main character has only a small hand bone to work with. “She identified the person’s age and sex based off that little bone,” says Sydney, “And you can’t, there’s no way you can identify anything other than if they have arthritis.”

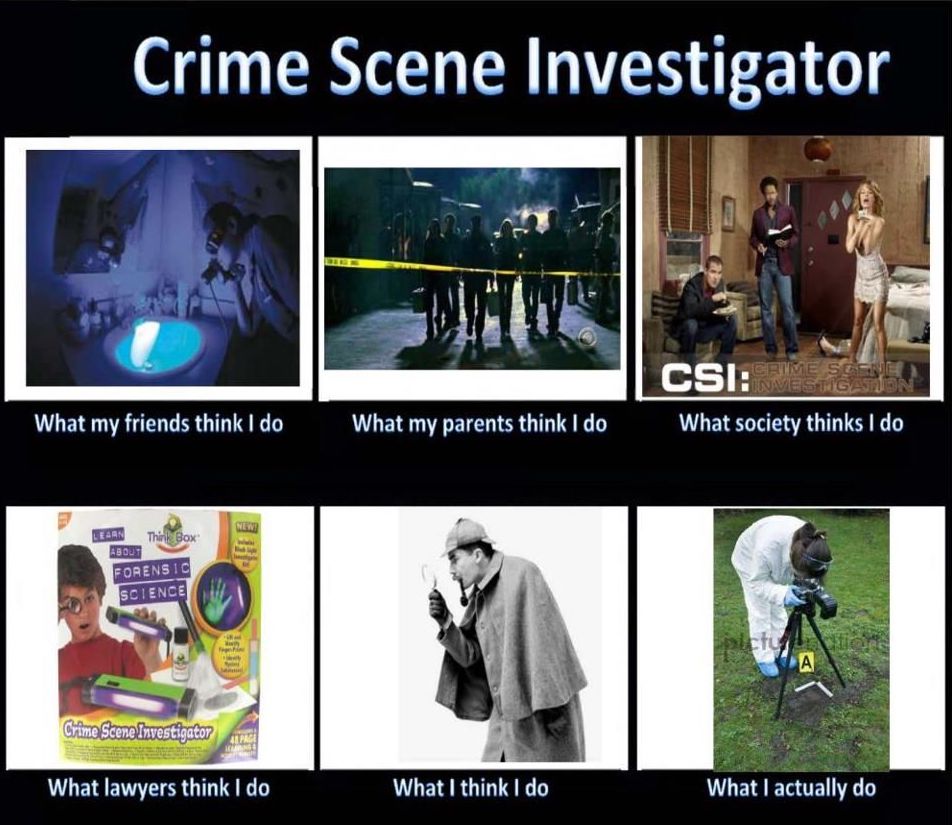

A CSI example of the “What I Do” meme. Processing a crime scene can take hours or even days and the angles and type of photos taken are very specific.

Friends and family of forensic scientists make assumptions about what they do for a living based on popular TV shows. “Some think I am like Indiana Jones,” says Sydney about when people learn that she’s also studied archeology (which is different from anthropology). “They ignore the forensics part. They’re still romanticizing the idea about what I do. Some of my family and friends will text me pictures of bones and go ‘I think it’s human’ and I’m like ‘no, it’s not.’ That happens pretty frequently.”

Neither Sydney nor Roxanne chose their path based on what they saw on TV, instead of coming to their careers in a roundabout way. Sydney said that after graduating with an anthropology degree, “I started asking my professors ‘Can I help you? Can I read a book? What do I do about grad school?’ I kept saying yes to a lot of things, trying to expand my skills, my toolkit.”

They have both met people who got interested in the field because of the popularity of shows focused on forensic scientists. They say it’s important to know what you’re getting into. If you’re interested in becoming a forensic scientist, make sure to research what the job really entails rather than relying on Hollywood’s depiction.

Both have Master’s degrees and some members of their team have a Ph.D. and other specialized certifications.

Though working with human remains and crime scene evidence takes an emotional toll, it can be very rewarding. “Even though we deal with a lot of bad things, there can be a lot of good that can come from it,” says Roxanne. “It’s nice to know that people are trying to help people get their lives back together.”

![Sydney (bottom left) answers questions as part of events sponsored by the Fleet, bringing models of bones to represent her work. “The Angela-tron [in Bones] is really cool,” says Roxanne. “We don’t have a fun program like that where you can recreate everything.”](/sites/default/files/2021-01/forensics-montage-3.jpg)

Sydney (bottom left) answers questions as part of events sponsored by the Fleet, bringing models of bones to represent her work. “The Angela-tron [in Bones] is really cool,” says Roxanne. “We don’t have a fun program like that where you can recreate everything.”

Thanks to both Roxanne and Sydney for sharing what it’s like to work in the field of forensic science! Both are volunteers for The Fleet Science Center’s program Two Scientists Walk Into A Bar, which deploys scientists into the community to talk about their work and remind everyone that scientists are regular people.